Arizona State University issued the following announcement on Nov. 17

One of the most important issues for voters in any election is health care, and this year, with the fate of the Affordable Care Act in the hands of the Supreme Court, it was no doubt top of mind for many Americans.

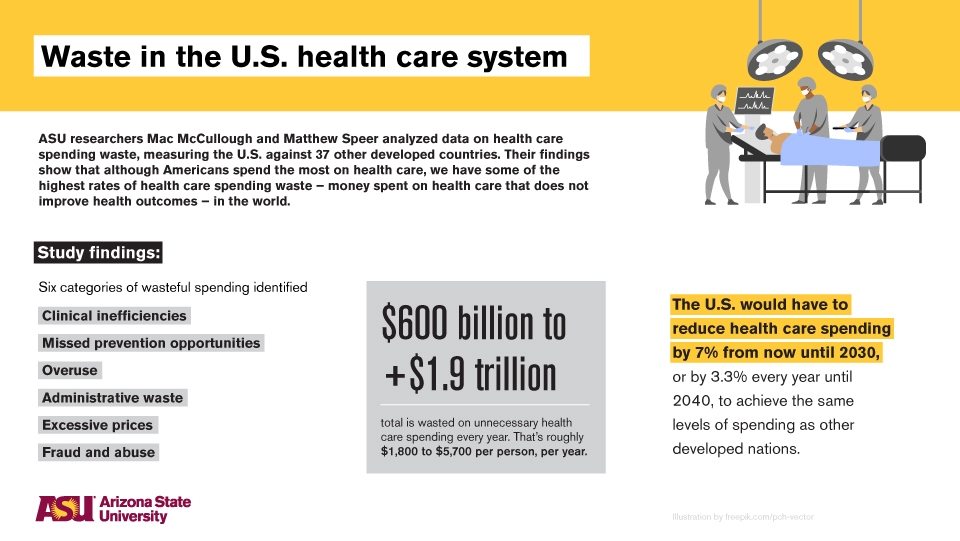

What might be surprising to some is that the U.S. has some of the highest rates of health care spending waste in the world.

ASU College of Health Solutions researchers Mac McCullough and Matthew Speer contributed two papers to a special edition of the American Journal of Public Health that explore the issue in further detail, measuring the U.S. against 37 other developed countries.

“We currently are, and have been for a long time now, leading the world in a category that isn't all that great, which is we spend an incredible amount of money on health care, but we don't see the kind of health outcomes, such as increased life expectancy, that you would expect if you were spending all that money,” McCullough said.

“On top of that, every dollar that we spend on health care is a dollar that can't be spent on something else. So that means other things like schools are going underfunded or, for a timelier example, public health agencies who are trying to fight COVID are going underfunded.”

McCullough’s paper found that the U.S. would have to reduce health care spending by 7% between now and 2030, or by 3.3% every year until 2040, to get to the same levels of spending as other developed countries. Speer's paper classified six categories of health care spending waste – clinical inefficiencies, missed prevention opportunities, overuse, administrative waste, excessive prices, and fraud and abuse – and found that between $600 billion to more than $1.9 trillion is wasted every year, or between $1,800 and $5,700 per person, per year.

Question: How do you hope your findings in these papers will improve the issue of health care spending waste in the U.S.?

McCullough: This isn't necessarily an issue that gets talked about as much as, say, having access to health insurance. We talk about that a lot, and how it would cost a lot of money to insure everyone, but almost never do we talk about the fact that if we trimmed some of the fat from this system, it would allow us to cover more people without asking more people to spend more money. It almost sounds too good to be true, that we could trim stuff that doesn't make us healthier and therefore broaden the tent to cover more people.

Speer: Globally, there's largely universal agreement that health care spending waste is simply defined as health care dollars that are spent that don't improve health outcomes. But even since before the Affordable Care Act, we’ve known that aggregate estimates that have looked into how much spending waste there is in the U.S. health care system have varied quite a bit. So what we tried to do was pull together all the aggregate estimates that exist for a better overall view of the situation. From there, we were better able to understand the different components of waste, which we did by synthesizing waste into six categories. So we’re hoping to present these findings as an opportunity for the government to invest in things that would improve public health outcomes. The actual mechanism for how we would translate these wasted health care dollars to improve health outcomes is obviously one that has a lot of different components to it and requires political will and feasibility.

Q: Of the six categories of health care spending waste, are there any in particular that cause more waste than others?

Speer: One of the largest categories, in terms of the magnitude of waste that we found when we synthesized those six categories, was overuse of services. The problem with trimming spending from that area is that it’s hard for people to get on board with the idea that we’re providing too many services or overtreating people, because the solution is to reduce the number of services that we're providing people. It’s just more difficult to sell someone on the idea that in order to reduce health care spending waste, we need to be performing less colonoscopies, for example, versus the idea that we need to be investigating more health care fraud abuse. So some solutions are just more palatable, and that determines what gets attention.

Q: What happens if we don't do anything to address wasteful health care spending?

McCullough: Unfortunately, our trajectory isn’t good. I think there's a competitiveness issue wherein American products cost more, in no small part because American companies have to pay higher prices for health care than companies in other parts of the world. And I anticipate that that would only get worse over the coming years. There will also be budget crises, both at the state and the federal levels. And eventually, there's going to be more demands on the Medicare system than dollars to fund the Medicare system. And there will come a time when the system simply runs out of money to keep doing business as usual – whether that's in two years or 20 years is probably fodder for a different research study. But absent some fundamental change, that’s what’s in the cards.

Q: How might the results of this year’s presidential election affect health care spending in the U.S.?

Speer: The outcome of this election could definitely have a significant impact on where health care expenditure goes. Fortunately, there is bipartisan support behind things like further regulating growth prices, prices being one of those six categories that we identified, and others have, as well. There is also bipartisan support behind improving health outcomes and decreasing health care costs. Now, where different candidates stand on how they would address those issues remains to be seen. But either way, I think that it's at least somewhat reassuring to know that there is bipartisan support and there is at least some agreement, and that's half the battle.

McCullough: I think it's important to consider not just the presidential election, but also what the Senate and the House will looked like. And then there’s also this looming case in the Supreme Court about whether to keep or strike the entirety of the ACA. So I think a lot of the direction for future health care policy will depend on that.

Q: What’s the key takeaway here?

Speer: The cost of a poorly performing and overly expensive health care system is detrimental to both public health and health equity. So seizing upon this moment that we find ourselves in, with the recent election and also the fallout of COVID-19, I think there is a great opportunity for us to make change, and we shouldn't waste it. We should see this as a moment to try to come together in pursuit of improved health equity and better public health outcomes.

McCullough: Aside from our papers, there's other evidence in this same special issue of the journal that too much health care can actually cause harm to our health. At the same time, it’s important to point out that health care spending waste isn’t necessarily the patient’s fault. If you've ever gone to the hospital and a month later received a bill that was 10 times what you thought it would cost, then you know that it wasn’t just because you were using too many services. The real problem is that we have this convoluted health care system that sets things up in a way that's really a no-win situation for a patient. Instead of being asked to pay a reasonable amount of money for a service, you're asked to pay some astronomical amount, and then you've got to go back and forth with all these different health insurance departments to adjudicate these disagreements about price, and that costs money, too. So one of the key things to consider is that we have all collectively designed a system that isn't working all that well, and we have an opportunity to change it in a way that will allow more people to benefit. And we need to keep an open mind about how we can do that.

Original source can be found here.

Source: Arizona State University

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up